In the mid-1980s, the wealthiest one percent owned an already disproportionate 16% of the country’s assets. As far as we can tell from limited data; the figure has skyrocketed since then to 25%.

Among the causes of this rise are the privatisation of previously public assets, the government’s failure to ensure the housing market works for everyone, and other changes brought in as we shifted to a pro-market, hyper-individualist mindset in the 1980s and 1990s.

THE RISE OF BUSINESS

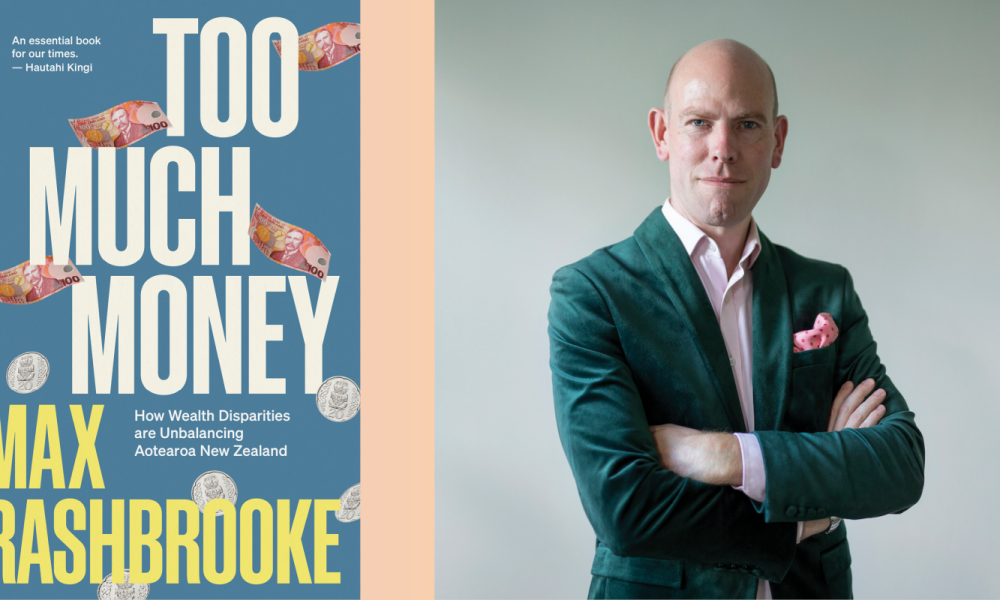

Another major cause, as I outline in my new book Too Much Money: How Wealth Disparities Are Unbalancing Aotearoa New Zealand, is the shifting power balance in the workplace.

In the last 40 years, the power of employers has risen sharply, particularly due to their increased status in public debates and their ability to move (or threaten to move) operations offshore if they do not like government policies. Conversely, the power of workers has diminished as the numbers covered by trade unions has fallen from 70% to just 17%.

As the former CTU economist Bill Rosenberg has shown, if wage and salary earners had retained the share of company revenue that they enjoyed in the 1980s, the average wage would now be around $14,000 a year higher. (The story is roughly the same if one looks at the way that wages have failed to keep up with productivity gains.) That company revenue goes instead to business owners – to capital rather than labour, in technical terms.

GROWING INEQUALITY

The result is that business owners’ wealth rises (assuming they save even a small percentage of that increased revenue), while wage and salary earners struggle to save out of their inadequate pay.

Wealth disparities widen. And since wealth now buys other advantages – better housing, enhanced political power, greater opportunities for one’s children – inequalities in well-being also grow, disparities are passed down the generations, and social and class divisions become entrenched.

A FAIR GO

If workplace dynamics are at the heart of this widened inequality, so too are they central to the solutions. Fair Pay Agreements and pay equity settlements can strengthen workers’ bargaining power and raise salaries for those whose pay packets have long been inadequate.

Further changes will be needed, though: perhaps something along the lines of the ‘union default’ idea being promoted by Waikato University’s Mark Harcourt, in which employees would be automatically enrolled in a union and would have to consciously opt out, as they do with KiwiSaver.

More broadly, renewed investment in core public services like education and health – what I call ‘the engines of opportunity’ – is needed to ensure that life chances are close to being genuinely equal and the fabled ‘fair go’ becomes more than just a slogan.

Too Much Money is available from your local bookstore or www.bwb.co.nz/books/too-much-money

You can win a copy if you tell us what proportion of the country’s assets did the wealthiest one percent own in the 1980s. Email editor@psa.org.nz to go into the draw.